by Janet Z. Li

Graphic design by Genevieve Groulx

When we think about infectious diseases, we tend to focus on the biological aspects–the “science” behind it. This is likely because historically, they have demonstrated the potential for widespread damage, in some cases resulting in fatalities as high as 60% of populations, as seen during the 14th century European Black Plague.1 In modern times, infectious diseases continue to be one of the leading causes of death worldwide, particularly in lower income countries and amongst younger individuals.2 Over the past few years, the entire world was brutally reminded of the vicious reality that is living amidst a pandemic, with around 104 million cases of COVID-19 having been reported in North America as of April 2022.3 Beyond the physical implications of acquiring an infectious disease, the biopsychosocial repercussions are equally as far-reaching and detrimental, despite rarely being talked about.

Infectious diseases bring extensive harmful impact, encompassing the general public and already vulnerable populations. During the COVID-19 pandemic, social distancing and isolation regulations minimized face-to-face contact, promoting significant increases in depression amongst the general population.4 Furthermore, fear of infection was a significant contributor for anxiety rate spikes. In combination with other factors related to lethargy and grief, the overbearing trepidation of contraction caused pre-existing social divides to deepen at dramatic rates.5 Trauma expert Steven Hobfoll notes that “the human brain searches gains for hidden losses”, meaning that people are more likely to think about the bad as opposed to the good,6 a phenomenon that is even more prevalent in times of uncertainty.

At a population level, social consequences may arise as a result of emotional fluctuations and can manifest as empathy gaps. Also known as cognitive biases, these are systemic errors that arise when people’s judgement deviates from their norm, and they exist in different contexts.4 One example is where individuals are less likely to help outgroup members as opposed to ingroup members.4 This was particularly visible when looking at pro-vaccination and anti-vaccination groups, demonstrating this natural human phenomena getting disproportionately escalated in times of crises,4 whereas in a more neutral state, they may be less prone to externalization. During the pandemic, an increase in susceptibility to others’ criticism has also been found, relating to the concept of other-focused concerns,4 when we focus on how others perceive us to be.

Another social ramification of infectious diseases are looping effects. This refers to how beliefs, when interacting with physiological processes, can result in disparate outcomes in different cultural contexts.7 In situations of tension and risk of spread, such as a pandemic, individuals’ beliefs about how to balance health and economy, trust in political or medical authorities, and ingrained customs are core values that can be either re-shaped or fortified when faced with adversity. These unstable shifts contribute to the rising outbursts, additionally fueled by widespread pandemic-induced vulnerability and a lack of a visible endpoint.8 Societal trust has plummeted in the last few years and researchers have begun to see the repercussions of the ‘rudeness epidemic’ that is just as contagious as an infectious disease.6

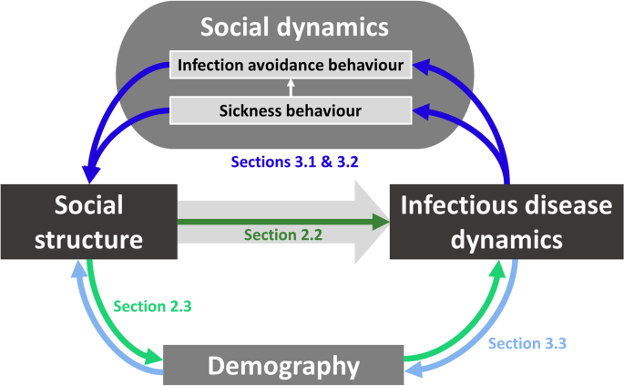

Sociologists and epidemiologists have studied the negative societal responses to a threat as natural collective behavior. In fact, some argue that the ways in which individuals vary in their social behavior and patterns of these contact networks actually mitigate the variation of disease dynamics.8 Although seemingly stochastic, the route of infectious disease transmission is actually highly predictable when factoring in known elements such as age or geography.9 Research suggests that behavioral responses to disease follow one of two patterns: to cause local pathogen extinction and epidemic burn-out, or naturally push a system towards more stable endemic disease dynamics. Broadly speaking, there are two relevant categories of behaviors, the sickness behavior of infected individuals and the behavior shown by uninfected individuals towards those with symptoms of infection. The latter includes important concepts of avoidance and empathy, both of which are strongly influenced by personality traits which are normally seen as stable throughout life but can be negatively exacerbated by perceived danger. Known as the ‘parasite-stress model’, the protective behaviors that humans display in response to illness aversion comes at the expense of intergroup relationships.7 In modern society, avoidance of unfamiliar outgroup members can ultimately lead to intensified stereotyped perceptions, prejudiced attitudes and feelings, and discriminatory behavior without guaranteed reduced risk of infection.7

Psychologist and professor Dr. David Rosmarin of Harvard Medical School states that during COVID-19, there was significantly increased anger as an artefact of the heightened tension.10 The recurring cycle of anxiety and depression, often manifesting as anger, has been explained from a clinical standpoint by classifying anger as a primary emotion, but often expressed in secondary ways, meaning it is more intensive and defensive.10 With the pandemic making people more on edge, this dynamic may be involved in the increase of domestic violence and homicide crimes over the last few years.10,11 Faced with sickness, daily issues may diminish in importance, unveiling the fragility and malleability of our emotional strength. We are able to see the ugly side of humanity more clearly and how when confronted with infectious diseases, we have less control than we think.

In a way, infectious diseases equalize us, since it transcends our man-made categorizations of social, economic, and demographic statuses. However, underlying this seemingly equitable illusion, pre-existing divisions are deepening at accelerated rates. We are only beginning to realize the effects of infectious disease on our biopsychosocial actions. To put it simply, our current tendency to focus on “under the skin” phenomena needs to be expanded to include the crucial aspect of what happens “outside the skin” before we can fully understand just how toxic we are.

References

- Martin J. The Black Death [Internet]. Uiowa.edu. 2017. Available from: http://hosted.lib.uiowa/uiowa.edu/histmed/plague/

- Baylor College of Medicine. Introduction to Infectious Diseases [Internet]. Baylor College of Medicine. 2016. Available from: https://www.bcm.edu/departments/molecular-virology-and-microbiology/emerging-infections-and-biodefense/introduction-to-infectious-diseases

- COVID-19/Coronavirus Real Time Updates With Credible Sources in US and Canada | 1Point3Acres [Internet]. Coronavirus.1point3acres.com. Available from: https://coronavirus.1point3acres.com/en

- Gaertmer SL, Dovidio JF, Anastaso PA, Bachman BA, Rust MC. The Common Ingroup Identity Model: Recategorization and the Reduction of Intergroup Bias. European Review of Social Psychology. 1993 Jan;4(1):1-26.

- Wilson ME. Geography of Infectious Diseases. Infectious Diseases [Internet]. 2017;938-947.e1. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7150158/

- The pandemic has caused nearly two years of collective trauma. Many people are near a breaking point. [Internet]. Washington Post. 2021. Available from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2021/12/24/collective-trauma-public-outbursts/

- Bayeh R, Yampolsky MA, Ryder AG. The Social Lives of Infectious Diseases: Why Culture Matters to COVID-19. Frontiers in Psychology. 2021 Sep 23;12

- Silk MJ, Fefferman NH. The role of social structure and dynamics in the maintenance of endemic disease. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 2021 Aug;75(8)

- Wilson ME. Geography of Infectious Diseases. Infectious Diseases [Internet]. 2017;938-947.e1. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7150158/

- Writer APHS. A closer look at America’s pandemic-fueled anger [Internet]. Harvard Gazette. 2020. Available from: https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2020/08/a-closer-look-at-americas-pandemic-fueled-anger/

- Nivette AE, Zahnow R, Aguilar R, Ahven A, Amram S, Ariel B, et al. A global analysis of the impact of COVID-19 stay-at-home restrictions on crime. Nature Human Behaviour [Internet]. 2021 Jul 1;5(7):868–77. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41562-021-01139-z

You must be logged in to post a comment.